The story through which Hawaii became a state in 1959 usually mythologizes a heroic effort by the Statehood Commission and the lobbying efforts of Territorial representative John Burns, and highlights the hurdles that Congress confronted before eventually voting for Hawaii’s statehood. These hurdles mainly involve racist bigotry and communist allegations along with various facets of organized labor, particularly the ILWU, the International Longshoreman’s and Warehouseman’s Union.

However, the retelling of the statehood process has left out those who did not, for whatever reason, participate in the plebiscite vote, the process adhering to the democratic ideals the United States was at that time trying to convey as its foreign policy strategy. Also, the mythology of Hawaii’s statehood story fails to adequately discuss the colonial/territorial history from the perspective of the United State’s obligation to educate and generally provide the necessary care mandated by the United Nations Charter of which the U.S. ratified in 1946.

One of the many obligations as stated in U.N. Resolution 742 in 1953 declares that one of the “factors indicative of the attainment of independence or of other separate systems of self-government,” is “freedom of choosing on the basis of the right of self-determination of peoples between several possibilities including independence.”

There is little to suggest that Hawaii’s plebiscite, offering only a choice between “statehood” or “to remain a territory,” fulfills the international mandate. Also, there is little to suggest that residents of Hawaii were properly educated on the process or understood the importance of the plebiscite and what rights were available to the population.

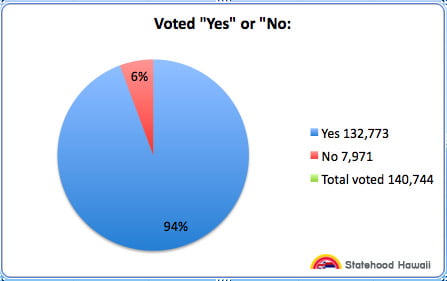

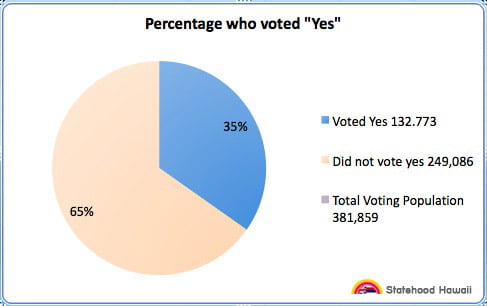

As the state insists that 94% of the voters voted for statehood, nowhere do they mention that of those eligible to vote, only 35% actively voted for statehood, as most Hawaii residents did not vote.

On March 18, 1959, the day Congress passed the Admission Act, Joseph F. Smith, Professor of Speech and an advocate of statehood at the University of Hawaii, sent a letter to Governor Quinn describing a recent study he conducted.

He wrote, “I venture to predict that one of the most surprising features of our forthcoming election will be the number of votes opposing statehood, plus the number of ballots which will carry neither yes or no votes.” Further he observed, “only three of the students were actively in favor of statehood, and the remainder were either apathetic, saying, ‘it will make no difference,’ or definitely opposed. I think, unquestionably, these youngsters reflect the attitude of their parents.”

This attitude of apathy reflects the fact that Territorial Governors were appointed by a U.S. President that residents of Hawaii were barred from voting for.

If the idea of Hawaii failing to attain statehood in 1959 seems implausible, one should also consider the viewpoints of Kamokila Campbell where she felt that Statehood would turn Hawaii into a Japanese dominated “menace” controlled by the Big Five; or ILWU union leader Jack Hall, when in 1953, he challenged the race-baiting perspective while coming out in favor of Hawaii becoming a commonwealth rather than a state, or when he introduced the rank-and-file to options of Independence via the U.N. Charter during the 1951 ILWU, Local 142 proceedings.

Even as early as 1947, writing for The Dispatcher, Jack Hall makes reference to a “King Kamehameha-ites” political party. The 15 years between the end of WWII and Statehood was a dynamic time, and challenges to international law, international labor, and the beginning of the United State’s dominance in the world set the backdrop to a long and vigorous debate on the issue of colonialism.

That this debate should, on July 27th 1959, culminate into a ten-word question to be followed by a “yes” or “no” is not without controversy. On June 27th, 1959, Hawaii held a plebiscite to determine whether the overall population of the Territory of Hawaii sought Statehood.

The final tallied vote, as was signed by Edward E. Johnston, the Secretary of State on July 2nd, 1959 declared the cumulative votes cast on all the islands was 132,773 in favor of statehood, while 7,971 opposed it. What these numbers indicate is that a total of 140,744 people voted either “yes” or “no” for Proposition 1 which read, “Shall Hawaii immediately be granted into the Union as a State?” (Figure 1).

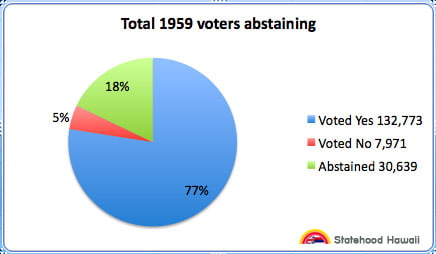

According to the State of Hawaii Data Book, Voter Turnout for the 1959 General Election was 171, 383, which reported that 30,639 or 18% of those who voted abstained, voting neither “yes” nor “no” on the plebiscite and simply voted for their representative in the General Election to which the plebiscite had been attached. So by including all who voted in the general election, only 77% really voted for statehood. (Figure 2).

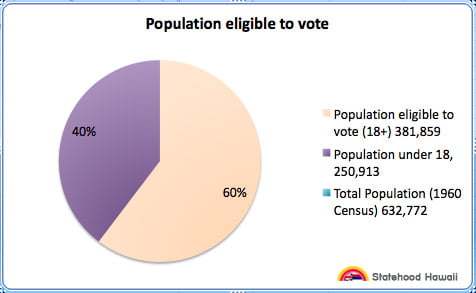

The total population of Hawaii from the nearest 1960 Census data reports a population of 632,772, with the median age being 38. Sixty percent of the population were of voting age and 381,859 were eligible to vote. (Figure 3).

Examining the assertion that 94% of Hawaii’s citizens voted for statehood, actual numbers reveal a much smaller percentage and the numbers suggest that only 35% of eligible voters actively sought statehood. (figure 4).

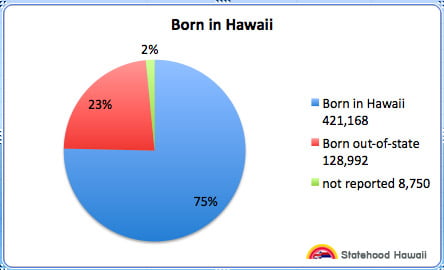

When you take into account Tables 5 and 6 below, what further arguments can be constructed regarding residency and race that might reframe the plebiscite narrative? Relevant factors on Residency and Race The following chart shows that 23% of the population were born out-of-state at the time the 1960 census was taken, which at the time of the plebiscite, and taking into account age discrepancy, still suggests a substantial sampling of non-native born residents potentially participating in the plebiscite vote (Figure 5).

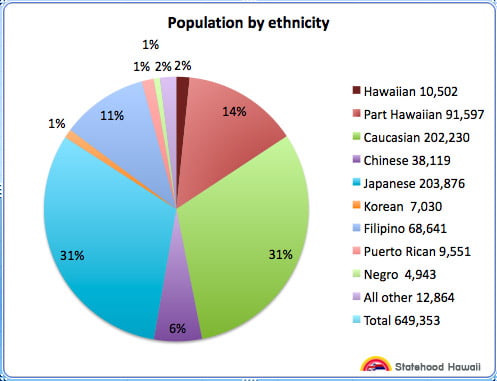

In Figure 6, considering Hawaii’s ethnic population at that time, Kamokila Campbell’s assertion that the Japanese vote would swing statehood was way off the mark considering that the majority of Japanese did not vote in the plebiscite. The same can also be noted for the Caucasian vote (which includes the Portuguese). Figure 6

Although one could assert that those who voted in the plebiscite, voted along these residential or racial lines, further examination on the plebiscite data reveals that except for the votes tallied from the island of Ni’ihau which was entirely native Hawaiian (there were 70 “no” votes and 18 “yes”), the large percentage of votes cast precinct by precinct reveals that an overwhelming majority of those who did vote in the plebiscite voted in favor of immediate Statehood.

There were however, certain district particularities for example, the district that registered the most “no” votes came from the more affluent and caucasian dominated Diamond Head/Kahala district, but there is little to suggest that there was any one determinate race or class that voted “Yes” or “No” in the plebiscite. More critique here and here.

Looking at these charts and statistics, the question that begs examination is: why did Dag Hammarskjold, the United Nations Secretary-General in 1959, accept Resolution 1469 (December 1959), the “Cessation of the transmission of information under Article 73 e of the Charter in respect of Alaska and Hawaii?”

The U.N. General Assembly, particularly the Fourth Committee (the committee responsible for Non-Self-Governing Territories under Chapter XI), as well as the specialized agencies like UNESCO, WHO, and the ILO that studied the information transmitted under Article 73e, were entrusted to study this data and challenge the blatant aberrations to the process outlined by the United Nations regarding the removal of territories from the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

Comparing the relatively low voter turnout and the peculiarities with race and residency in Hawaii’s demographics reveal a contradiction to the process used by the United Nations to remove territories from the list. In the fifteen years prior to statehood, the General Assembly debated the removal of many of the Non-Self-Governing Territories, especially when there are inconsistencies with the voting mechanism– specifically over voter turnout and indigenous peoples. In South Africa for example, when the U.K. first tried to remove South Africa in 1949, the U.K. administering power submitted a vote that revealed wide support in favor of annexation. However, the voting record showed that the majority of Africaans did not vote and the application was thus rejected. But in 1961, by a whites-only referendum, South Africa left the British commonwealth to become a Republic. The harsh language of the 1961 U.N. resolution 1598 “Affirms that the racial policies being pursued by the Government of the Union of South Africa are a flagrant violation of the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and are inconsistent with the obligations of a Member State.”

An example of a vote held within the guidelines of the United Nations was the U.S. colony, Puerto Rico. Out of a total of 873,085 eligible voters, 640,714 went to the polls in 1953, and the votes were cast and split among options for commonwealth/statehood/independence. More that 3/4 of the eligible population voted, which was in accordance with the Sacred Trust that was mandated with Chapter XI of the Charter. Almost without controversy, Puerto Rico voted for commonwealth (the Puerto Rican controversy lay with the voting on its Constitution).

Again, Hawaii had only 1/3 of the eligible voting population voting and that is a sound basis for contestation.

Arnie Saiki– Project Director

Sources:

State Department Records. Foreign Relations, 1952-1954, Volume III pp. 1211-38.

United Nations Charter and Resolutions 66, 142, 742, 1469, 1598.

United Nations General Assembly Yearbook, 1948. p 209. “Statement by Departmental Representaitve Before the Subcommittee on Territories and Insular Affairs of the the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on the Question of Admisssion of Alaska as a State of the Union” (Including Replies) March 12, 1957.

Department of State Records 1960 Census Report. Hawaii State Archives.

“Hawaii Red Hunt Aims At Destroying ILWU,” The Dispatcher, ILWU, Vol.5, No. 26, December 26, 1947, page 8.

“State of Hawaii Data Book” Legislative Reference Bureau. Plebiscite Record: Hawaiian Collection, U.H. Library. Information from Non-Self-Governing Territories: Summary and Analysis of Information Transmitted Under Article 73 e of the Charter.

Report of the Secretary General May 6, 1958. A/3815 U.N. Records Information from Non-Self-Governing Territories: Summary and Analysis of Information Transmitted Under Article 73 e of the Charter.

Report of the Secretary General: Pacific Territories. Hawaii. March 6, 1959. A/4088 U.N. Records “Communication from the Government of the United States of America concerning Alaska and Hawaii” A/C.4/L.632. U.N. Records “Draft Guidance Paper on Puerto Rico for Tenth Session of Organization of American States” December 1, 1953. Department of State.

“Kamokila Opposes Island Statehood,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin. January 17, 1946.

“Statehood for the Territory of Hawaii: A Statement in behalf of the ILWU, CIO,” Regional Director for Hawaii, Jack Hall. March 1947.

“Commonwealth Status for Islands Backed by I.L.W.U International” Honolulu Star-Bulletin. July 11, 1956.

“Correspondence between Joseph F. Smith and Governor Quinn,” Hawaii State Archives. March 18, 1959